Topic 24: Elucidating Gas Molecular Adsorption Phenomena by Nanoporous Materials

Unveiling the Secrets of Porous Coordination Polymers that Actively Adsorb Gases

Activated carbon, which has numerous small holes (nanopores) on its surface, is commonly used for deodorization and water purification due to its high capacity to absorb organic matter. Materials with such pores are collectively referred to as nanoporous materials. In particular, porous coordination polymers, which are synthesized from metal ions and organic molecules, have recently attracted increased attention. The advantages of porous coordination polymers are they can store various gases, including hydrogen, at a high density and various functions can be implemented. At SPring-8, researchers have been leading the world to elucidate the mechanisms by which the nanopores of porous coordination polymers adsorb gases. This topic presents examples of these remarkable accomplishments as well as research outcomes on hydrogen storage alloys.

Designing Nanoporous Materials with Desired Functions

In February 2002, a group led by Dr. Susumu Kitagawa (Professor, Kyoto University, Japan) initiated research on orderly adsorbing oxygen with nanoporous materials. This project was developed in collaboration with Dr. Masaki Takata1) (Associate Professor, Nagoya University, Japan), Dr. Tatsuo Kobayashi (Professor, Osaka University, Japan), and Dr. Makoto Sakata2) (Professor, Nagoya University). These nanoporous materials, which are porous coordination polymers composed of metal ions, such as copper and cobalt, and organic molecules, are capable of storing various gases at room temperature. Moreover, the area of several grams of nanoporous materials has a surface area equivalent to a basketball court or in some cases a soccer field. “We strived to demonstrate that nanoporous materials can be fully controlled to store gases,” says Dr. Kitagawa.

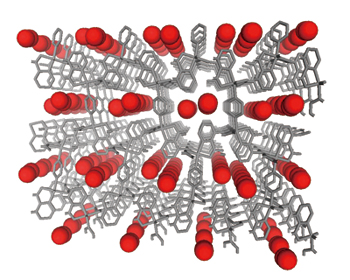

They examined a copper coordination polymer (CPL-1) because the pores of CPL-1 are 0.4 × 0.6 nm (nm = 10-9 m) in size and adsorb oxygen. Synchrotron radiation diffraction experiments on CPL-1 powders cooled to -183 °C were conducted at the Power Diffraction Beamline (BL02B2). Analyses of the diffraction patterns, which indicate the adsorption of oxygen molecules, using the data processing algorithm developed by the Nagoya University group revealed that the oxygen molecules in solid-like aggregation states are perfectly aligned in the pores. Additionally, they found that oxygen molecules aligned in a double line parallel to the direction of the pores form a ladder structure with a minimum intermolecular distance of ~0.32 nm (Fig. 1). Their new findings were published in Science (December 2002).

1) Currently Chief Scientist at RIKEN.

2) Currently Professor Emeritus at Nagoya University, Japan.

Oxygen molecules (red) are regularly aligned in the pores formed in CPL-1.

Anticipating High Hydrogen Adsorption Capacity for Fuel Cells

If hydrogen is stored in porous coordination polymers, which are easily designed and synthesized, then porous polymers should be applicable to fuel cells. In April 2003, Dr. Kitagawa in collaboration with Dr. Yoshiki Kubota3) (Associate Professor, Osaka Women's University, Japan), Dr. Masaki Takata4) (Chief Scientist, the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute), and colleagues, conducted experiments to directly observe hydrogen molecules by adsorbing them into the pores of CPL-1, which was previously used in an oxygen adsorption experiment. Observing a hydrogen atom, which has only one electron, with X-rays is typically extremely difficult. “Understanding the behavior of hydrogen molecules is necessary to synthesize nanoporous materials,” explains Dr. Kitagawa.

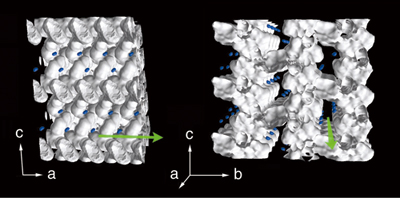

Although powder X-ray diffraction experiments were conducted at the Powder Diffraction Beamline (BL02B2), the amount of obtained data was very limited. To overcome this, Dr. Takata developed a new technique to effectively extract the electron density distributions from a small amount of data. The extracted distributions revealed that hydrogen molecules exist near oxygen atoms bound to copper atoms of porous coordination polymers (Fig. 2). Additionally, the pores have concavo-convex surfaces, and hydrogen molecules fit into the concave regions and move freely. These results suggest that porous coordination polymers may be an ideal molecular storage system if the pores and molecules have similar sizes. Their achievement was published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition (January 2005) and an image of their nanoporous material appeared on the front cover.

On the other hand, the most promising material to store hydrogen is a hydrogen storage alloy. In May 2001, Dr. Tatsuo Noritake (Chief Researcher, Toyota Central R&D Labs, Japan), Dr. Makoto Sakata (Professor Emeritus, Nagoya University), and colleagues analyzed the electron density distributions of a hydrogen storage alloy called magnesium hydride (MgH2). At that time, the amount of stored hydrogen in a hydrogen storage alloy was ~2% by weight, and consequently, the development of light alloys capable of storing more hydrogen was desired. Magnesium is light and has a hydrogen storage capacity of 7.6% by weight. However, MgH2 must be heated to >300 °C to release hydrogen. Dr. Norikate recalls back on that time, “To overcome this issue, we had to go back to the basics and examine the distribution of electrons responsible for binding in MgH2.”

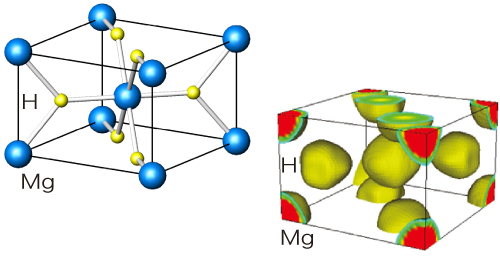

Their research group conducted experiments on MgH2 powders by irradiating highly brilliant X-rays at BL02B2, and determined the electron density distributions of hydrogen (Fig. 3). They noted that the number of electrons was peculiar. The magnesium region of MgH2 forms a sphere with a radius of 0.09 nm, which has 1.91 less electrons and becomes a positive ion, whereas the hydrogen region forms a sphere with a radius of 0.1 nm, which has 0.26 more electrons and become a negative ion. Thus, magnesium and hydrogen are ionically bonded. Moreover, the overall electron density in MgH2 is very low and metallic bonds did not exist. MgH2 exhibits a weak covalent bond with overlapping magnesium and hydrogen electrons. “When MgH2 adsorbs hydrogen, the adsorbed hydrogen atoms become negative by attracting free electrons, and the magnesium atoms are ionically bonded with these hydrogen ions to become stable,” explains Dr. Noritake. Their research achievement was published in Applied Physics Letters (September 2002).

3) Currently Associate Professor at Osaka Prefecture University, Japan.

4) Currently Chief Scientist at RIKEN.

Blue dots denote hydrogen molecules. Hydrogen molecules are not situated at the center of the pore, but are closer to the pores' walls, and are regularly aligned regardless of the coordination polymer structure.

Yoshiki Kubota, Masaki Takata, Ryotaro Matsuda, Ryo Kitaura, Susumu Kitagawa, Kenichi Kato, Makoto Sakata, Tatsuo C. Kobayashi: Direct Observation of Hydrogen Molecules Adsorbed onto a Microporous Coordination Polymer; Angewandte Chemie International Edition; 2004, Vol. 44, page 922. Copyright Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Reproduced with permission.

Crystal structure of MgH2 (rutile-type structure) and surfaces of electron density at ρ= 0.3e/(0.1 nm)3 are depicted. An ionic bond is formed as magnesium and hydrogen become positive and negative ions, respectively.

Revealing the Adsorption States of Acetylene Gases

Dr. Kitagawa and colleagues conducted an experiment at BL02B where they revealed that acetylene gases interact with nanopores very strongly and are densely stored in the pores. Additionally, they determined that the adsorption processes contain several state changes. Their research results were published in Nature (July 2005).

“To utilize porous coordination polymers as adsorption materials for highly active gases, the states of the polymers after inserting gas molecules must be further elucidated,” explains Dr. Kitagawa. Consequently, Dr. Kitagawa and colleagues conducted experiments to investigate the adsorption processes of acetylene gases by nanoporous materials at BL02B2. In their experiments, copper coordination polymer crystals were loaded into a glass capillary (a very thin glass tube), and acetylene gases were inserted. Powder diffraction data were collected with a large Debye-Scherrer camera with a camera radius of 287 mm. Controlling pressure and temperature allowed diffraction data to be simultaneously detected through the 2D detectors.

They found that acetylene molecules form hydrogen bonds with oxygen atoms in the pore wall in a saturated phase, causing acetylene molecules to absorb into the pore walls with a high density. In contrast, the structure changes in the polymer crystal from an intermediate phase to a saturated phase are small, and the bonds between the acetylene molecules and the pore wall in the intermediate phase are much weaker than those in the saturated phase (Fig. 4). Additionally, after adsorption, the crystal lattices expand to an intermediate phase, and the pores start to deform. Upon reaching the saturated phase, the pores contract. These observations revealed that the copper coordination polymer crystal flexibly changes its structure through the interactions of the acetylene molecules with the pore wall to adsorb acetylene. This achievement was published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition (July 2006).

Due to its great potential in many applications (e.g., the low-pressure stable storage of natural gases, adsorption of greenhouse gases, separation of toxic materials, and superconductive or magnetic materials), the development of nanoporous materials is thus highly anticipated.

Views from the nanochannel direction. Negligible chemical bonding is observed between acetylene molecules (green) and neighboring oxygen atoms in both sides of the former.

References

1. R. Kitaura, S. Kitagawa, Y. Kubota, T. C. Kobayashi, K. Kindo, Y. Mita, A. Matsuo, M. Kobayashi, H. Chang, T. C. Ozawa, M. Suzuki, M. Sakata and M. Takata; Science, 298, 2358 (2002)

2. Y. Kubota, M. Takata, R. Matsuda, R. Kitaura, S. Kitagawa, K. Kato, M. Sakata and T. C. Kobayashi; Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 44, 920 (2004)

3. T. Noritake, M. Aoki, S. Towata, Y. Seno, Y. Hirose, E. Nishibori, M. Takata, and M. Sakata; Appl. Phys. Lett., 81, 2008 (2002)

4. Y. Kubota, M. Takata, R. Matsuda, R. Kitaura, S. Kitagawa and T. C. Kobayashi; Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 45, 4932 (2006)